During your junior year physics, you have learned about the thermal expansion of solids and fluids. Although you might have not discussed the details of it all, it is not a counter-intuitive concept how materials expand at the addition of heat. To understand thermal expansion in its entirety, we have to discuss the molecular interaction. Proposed by Sir John Edward Lennard-Jones, the Lennard-Jones potential describes the potential energy of interaction between two non-bonding atoms or molecules based on their distance of separation. The potential equation accounts for the difference between attractive forces (dipole-dipole, dipole-induced dipole, and London interactions) and repulsive forces. To understand the interaction, let’s take the following example.

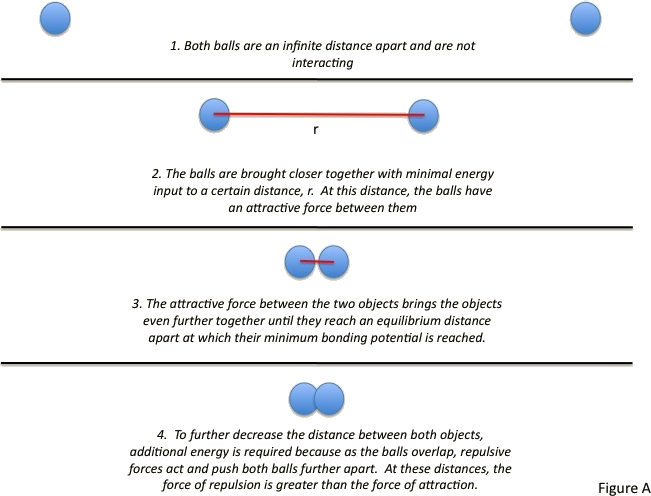

Imagine two rubber balls separated by a large distance. Both objects are far enough apart that they are not interacting. The two balls can be brought closer together with minimal energy, allowing interaction. The balls can continuously be brought closer together until they are touching. At this point, it becomes difficult to further decrease the distance between the two balls. To bring the balls any closer together, increasing amounts of energy must be added. This is because eventually, as the balls begin to invade each other’s space, they repel each other; the force of repulsion is far greater than the force of attraction. This scenario is similar to that which takes place in neutral atoms and molecules and is often described by the Lennard-Jones potential.

The Lennard-Jones model consists of two ’parts’; a steep repulsive term, and smoother attractive term, representing the London dispersion forces. Apart from being an important model in itself, the Lennard-Jones potential frequently forms one of ’building blocks’ of many force fields. It is worth mentioning that the 12-6 Lennard-Jones model is not the most faithful representation of the potential energy surface, but rather its use is widespread due to its computational expediency. The Lennard-Jones Potential is given by the following equation:

$$V(r)= 4 \varepsilon \left [ {\left (\dfrac{\sigma}{r} \right )}^{12}-{\left (\dfrac{\sigma}{r} \right )}^{6} \right] \label{1}$$

or is expressed as follows

$$V(r) = \frac{A}{r^{12}}- \dfrac{B}{r^6} \label{2}$$

where

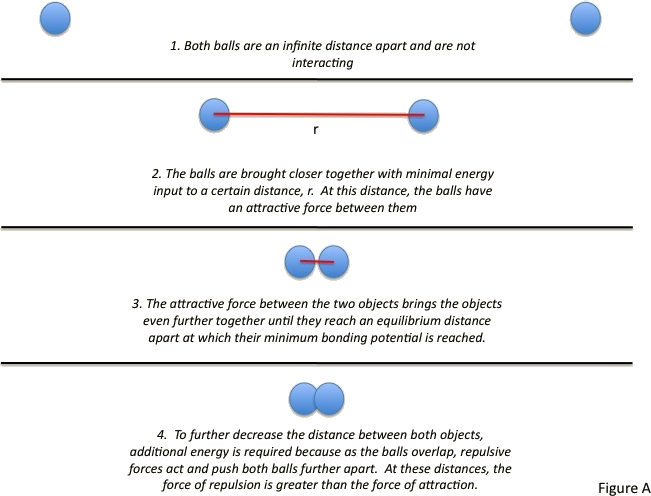

V is the intermolecular potential between the two atoms or molecules.

ε is the well depth and a measure of how strongly the two particles attract each other.

σ is the distance at which the intermolecular potential between the two particles is zero. It gives a measurement of how close two nonbonding particles can get and is thus referred to as the van der Waals radius. It is equal to one-half of the internuclear distance between nonbonding particles.

r is the distance of separation between both particles (measured from the center of one particle to the center of the other particle).

A = 4εσ12

B = 4εσ6

The Lennard-Jones potential is a function of the distance between the centers of two particles. When two non-bonding particles are an infinite distance apart, the possibility of them coming together and interacting is minimal. For simplicity’s sake, their bonding potential energy is considered zero. However, as the distance of separation decreases, the probability of interaction increases. The particles come closer together until they reach a region of separation where the two particles become bound; their bonding potential energy decreases from zero to a negative quantity. While the particles are bound, the distance between their centers continue to decrease until the particles reach an equilibrium, specified by the separation distance at which the minimum potential energy is reached.

If the two bound particles are further pressed together, past their equilibrium distance, repulsion begins to occur: the particles are so close together that their electrons are forced to occupy each other’s orbitals. Repulsion occurs as each particle attempts to retain the space in their respective orbitals. Despite the repulsive force between both particles, their bonding potential energy increases rapidly as the distance of separation decreases.

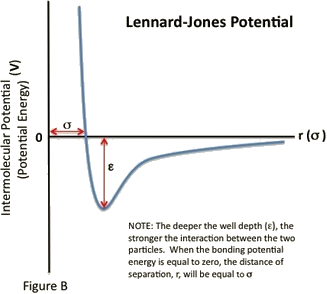

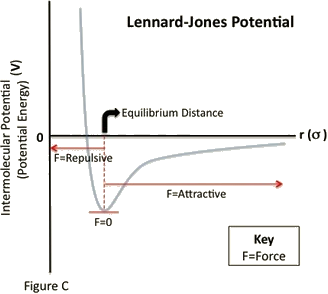

Like the bonding potential energy, the stability of an arrangement of atoms is a function of the Lennard-Jones separation distance. As the separation distance decreases below equilibrium, the potential energy becomes increasingly positive (indicating a repulsive force). Such a large potential energy is energetically unfavorable, as it indicates an overlapping of atomic orbitals. However, at long separation distances, the potential energy is negative and approaches zero as the separation distance increases to infinity (indicating an attractive force). This indicates that at long-range distances, the pair of atoms or molecules experiences a small stabilizing force. Lastly, as the separation between the two particles reaches a distance slightly greater than σ, the potential energy reaches a minimum value (indicating zero force). At this point, the pair of particles is most stable and will remain in that orientation until an external force is exerted upon it.

Recall that the force can be determined from the PE graph by taking the negative of the derivative (technically, the gradient):

$$F = -\dfrac{\nabla U}{\nabla r} \implies F = -\dfrac{\partial U}{\partial r}$$

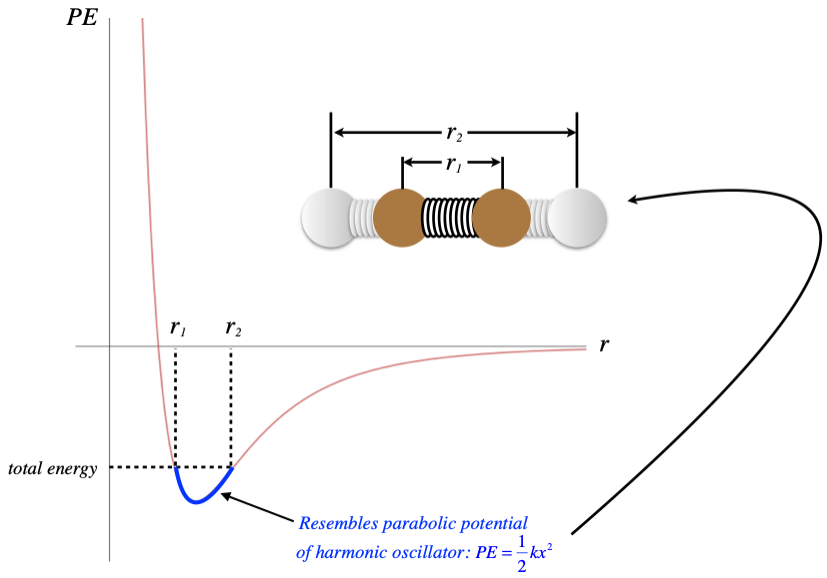

So the places on this curve that have negative slopes have positive forces, and the positive direction is in the +r-direction, which is a repulsive force. When the slope is positive, the force direction is negative, which is in the -r-direction and is therefore attractive. We therefore have a force that is alternately repulsive and attractive around a certain equilibrium position – near the bottom of the dip, usually called a potential well. The PE curve down there is closely approximated by a parabola, so the KE and PE of the particle combine to result in a physical system that looks very much like two particles bound together with a spring, with the equilibrium point of the spring being the separation of the particles associated with the bottom of the well.

We know that when we add energy to a spring system, the amplitude of the oscillations increases. The same is true here – the distance across the well widens. But unlike a spring system, this PE curve is not quite symmetric. When the energy of the particle-particle system is increased, the average separation actually increases. Keep in mind that when energy is added to a macroscopic system, it gets distributed through all the particles, raising all of their energies, and increasing all of their average separations. If we have N particles in a row, and the average separation increases by some small factor, then the overall length of this chain of particles increases by the same factor. While the amount of change on the microscopic level is incredibly small, it is measurable on the macroscopic level because there are so many particles.